Ukrainian civilians and journalists are tortured by Russia. This can happen here, we mustn't fool ourselves.

Cate Brown, Jarrett Ley, Catherine Belton and Anastacia Galouchka, “Washington Post”, 4/29/25

The body bag was delivered to Kyiv on a flatbed truck. There was an alphanumeric code stamped across the white shroud, followed by four Cyrillic letters: СПАС — a Russian abbreviation denoting “extensive damage to the coronary arteries.”

For most of the 757 Ukrainian bodies exchanged for Russian dead on Feb. 14, the Russian authorities had provided their counterparts in Kyiv with names of the deceased, nearly all male soldiers, and the dates they were killed. The final entry on the list handed to prosecutors said only “unidentified male.”

When forensic experts opened the bag, they found a female body. Her head was shaved, her neck bruised. There was a tag with her last name attached to one shin, and burn marks on her feet, according to officials familiar with an ongoing investigation by the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s Office. Medical examiners later found a broken rib and possible traces of electric shock. Some of her organs, including her brain, had been removed, officials said.

A DNA test confirmed that the body belonged to Viktoriia Roshchyna, a 27-year-old Ukrainian journalist who had disappeared into the Russian prison system after being detained while reporting in the occupied territories in August 2023. Roshchyna, the first Ukrainian journalist to die in Russian captivity, was reported dead in a curt note dated Oct. 2 and addressed by Russian authorities to her father, Volodymyr Roshchyn. But without any details on the cause of death, her father clung to hopes she might still be alive.

Before one of her last reporting trips, Roshchyn recalled, his daughter had carried a bulletproof vest and a pierced helmet into his home. He asked her to stay, but remembers only that she said, “I have to go.”

“When she decides to do something, she will do it,” her father said.

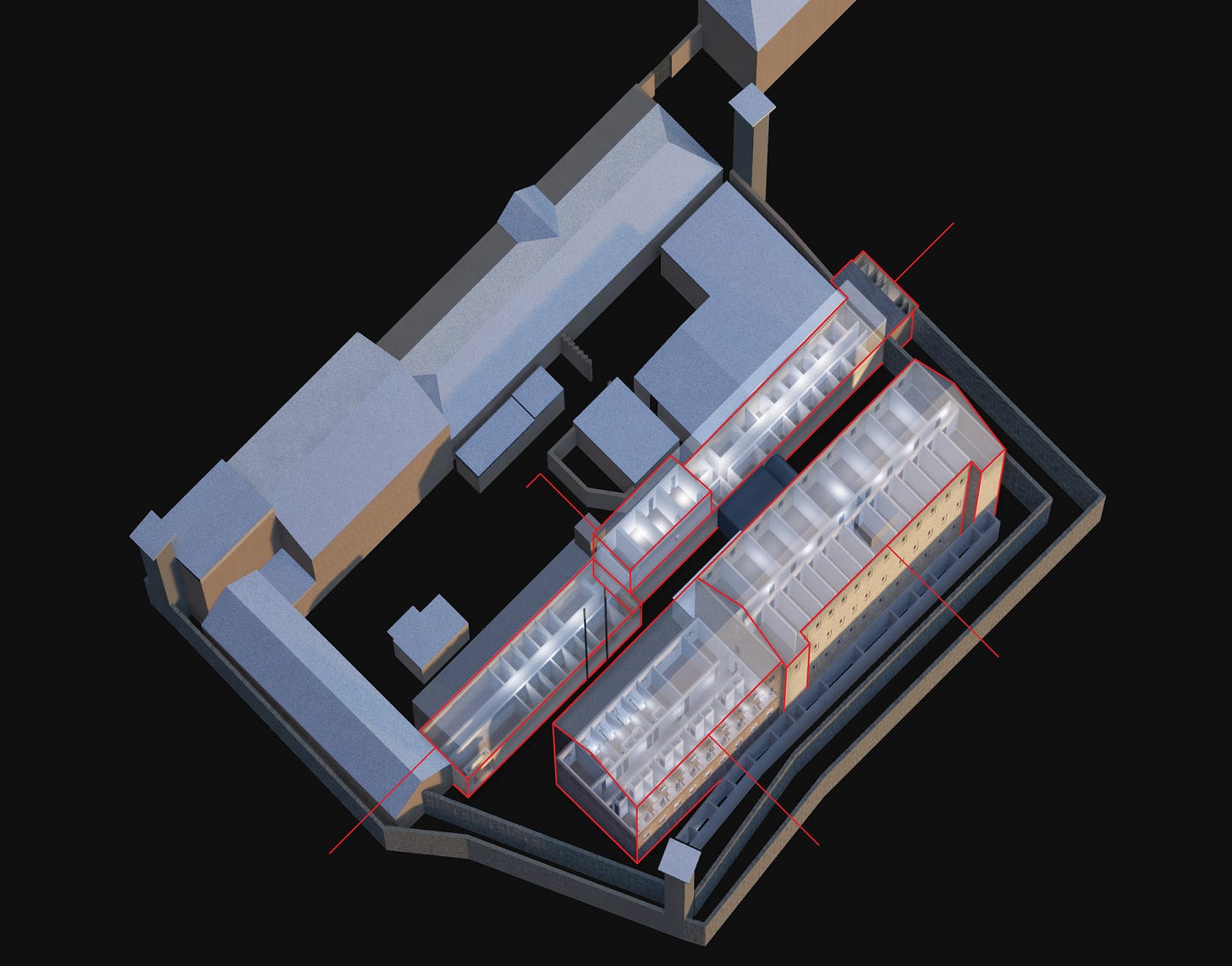

For much of the war, the former juvenile detention center at Taganrog has been a site of systematic physical and psychological abuse, according to a review of court records and prison procurement documents, as well as interviews with Ukrainian investigators, Russian lawyers, European intelligence officials and nine former Taganrog prisoners. Some people spoke on the condition of anonymity because of security concerns or to discuss sensitive material.

The Viktoriia Project

Launched shortly after Roshchyna’s death was announced on Oct. 10, the Viktoriia Project is a collaboration led by Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based nonprofit that continues the work of journalists who have been killed, imprisoned or threatened for their work. Forty-five reporters joined forces to investigate her death in Russian captivity and complete her reporting on Ukraine’s “ghost prisoners.”

The U.N. said Russia’s treatment of detainees is “disturbing and the scale is extreme.”

“I have documented serious cases of torture, including mock executions, all types of beatings, electricity being applied to ears and genitals and other parts of the body, waterboarding, as well as threats and actual rapes and sexual violence,” said Alice Edwards, the U.N.’s special rapporteur on torture. “Look, I’m calling this part of Russian war policy. It’s clear that it’s organized. It’s clear that it’s systematic.”

The Kremlin and the Russian prison service did not respond to requests for comment.

The treatment of detained Ukrainian civilians is one of the most brutal and least examined parts of the Kremlin’s prosecution of the war. Roshchyna wanted to expose this heavily camouflaged penal system, until her own disappearance and unexplained death became an emblem of Russia’s violation of the laws of war, officials, activists and lawyers said — with the prison at Taganrog, just over the border from occupied Ukraine, as Exhibit No. 1.

A coalition of 45 international journalists led by Paris-based Forbidden Stories and including The Washington Post has continued Roshchyna’s work and conducted a months-long investigation into her death, the Taganrog complex, and the network of prisons and ad hoc detention centers that stretches from occupied Ukraine to northern Russia.

Reporters identified 29 sites in occupied Ukraine and Russia where Ukrainian prisoners said they were subjected to torture and abuse.

Yevgeny Markevich, a prisoner of war held at Taganrog, remembers hearing Roshchyna speaking to the guards from her cell.

“She told the prison guards straight to their faces, ‘You are occupiers, you came into our country, you are murdering our people. ... I will never cooperate with you!’” Markevich said. “She was probably saved by the fact that she was a woman. If I had said something like that, they would have killed me on the spot.”

Mykhailo Chaplya, a 37-year-old former POW who spent two years at Taganrog, described seeing guards torture prisoners to the edge of their physical limits, but said he fears that “with Viktoriia, they went too far.”

A fearless reporter

Roshchyna was something of a lone wolf, colleagues said, a fearless, often obstinate reporter who pursued the kind of assignments that made others blanch.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, she was one of the only Ukrainian journalists to report from Russian-occupied territories, first for an online outlet, Hromadske, where she had been a courts reporter, and then as a freelancer, mostly for Ukrainska Pravda. [“Pravda” means “Truth”.]

“Since Feb. 22 the life of every Ukrainian has changed. ... Almost every citizen became a soldier, including journalists,” she said in a video message in October 2022 after receiving a Courage in Journalism Award from the International Women’s Media Foundation. “We have remained faithful to our mission, to convey the truth.”

Roshchyna began documenting Russian military incursions in southeast Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia region, including in the city of Enerhodar, the site of Europe’s largest nuclear power plant. On March 5, she and her driver came under fire as they passed within sight of Russian tanks, according to an alert from a press-safety monitor, and quickly abandoned their vehicle. Russian soldiers destroyed it, stealing her laptop and camera, while she hid for hours in a nearby building. Still, Roshchyna published a March 11 report documenting Enerhodar’s resilience, even as the Russian occupation of the city threatened her ability to leave.

“She took risks not for the sake of bravery or being recognized, but because she believed it was her duty,” said Nataliya Gumenyuk, a rare reporting partner at Hromadske.

Records show that Roshchyna embarked on a circuitous journey into the occupied territories the following month: first crossing into Poland, and then traveling on to Latvia by bus and eventually into Russia on July 26, 2023. She was traveling on a Ukrainian passport when she entered the Russian Federation, according to border documents. Given her profile as a journalist, Roshchyna’s ability to enter and travel through Russia remains a mystery — even her editor said she did not understand how Roshchyna was not stopped.

Disappeared into Taganrog

The cellmate recalls Roshchyna arriving at Taganrog in December 2023, in testimony provided to the Prosecutor General’s Office in Kyiv, which was reviewed by the consortium. The cellmate declined to speak to reporters. Taraniuk recalled temporarily living on the same block as five female medics from Mariupol.

Former detainees described constant surveillance within the cellblock.

HOPES OF RELEASE

In April 2024, after nearly eight months without news, Roshchyna’s father received word that his daughter was being held in Taganrog. Soon after, Russian authorities and the International Committee of the Red Cross confirmed that Roshchyna had been detained, according to a

On Oct. 10, Musaieva got a call from Roshchyna’s father. He’d received a letter from the Russian authorities stating that his daughter was dead.

Torture facility — floor 1; male and female cellblocks — floor 2